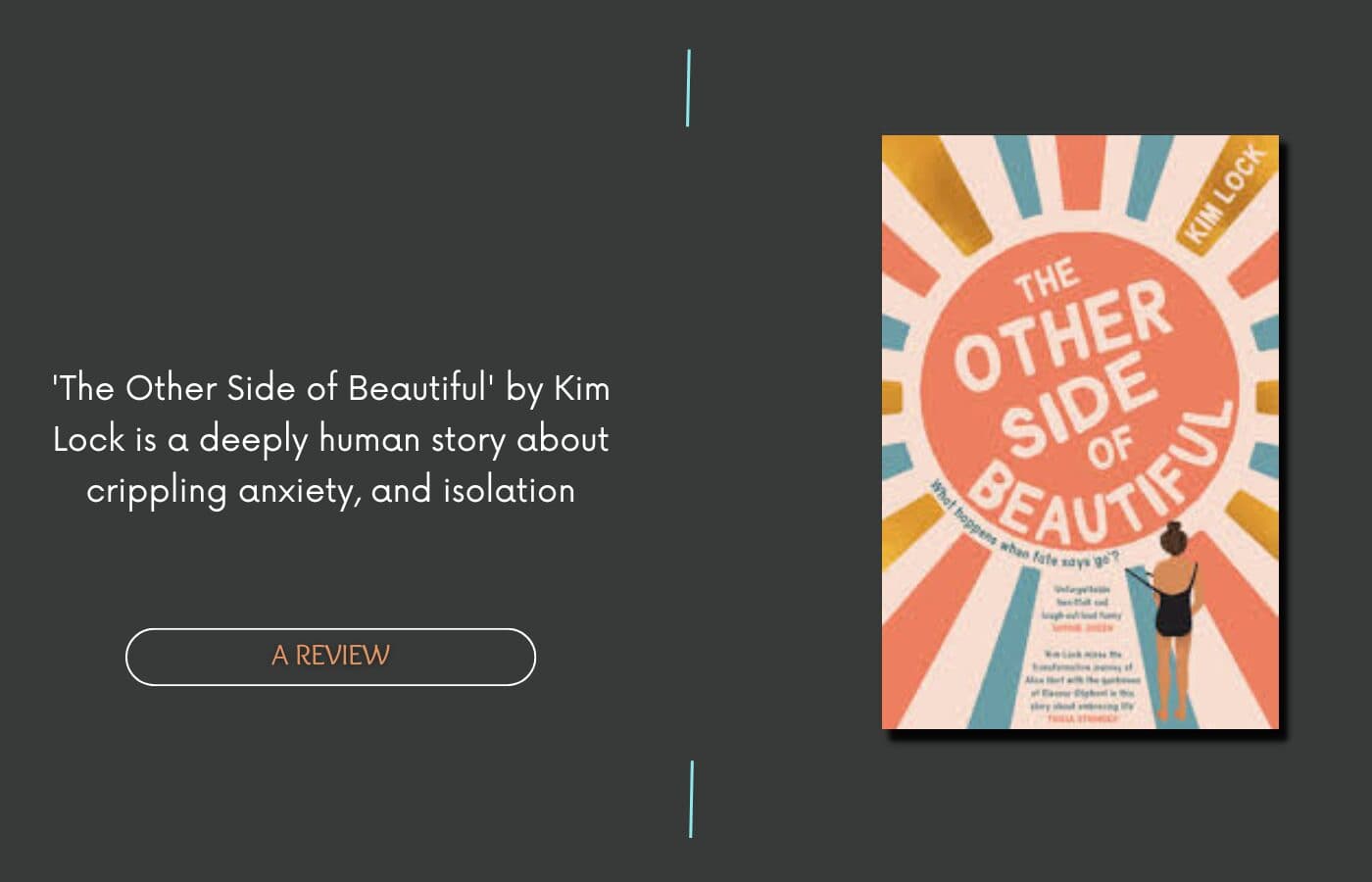

Before the fire, Mercy Blaine hadn’t left her house in two years. After the fire, with nothing but a reluctant heart and her dog Wasabi for company, she finds herself behind the wheel of a creaky campervan heading north towards Darwin. Forced to face a life outside four walls, she embarks on an unexpected journey through the Australian landscape, with no real plan beyond putting distance between herself and her old life.

Kim Lock’s quietly powerful novel, ‘The Other Side of Beautiful’ is a deeply human story about crippling anxiety, and isolation. Mercy’s story is about learning to breathe again when everything inside you has forgotten how. Mercy’s fears are rooted in the everyday moments that many take for granted like walking into a store, filling up gas at a petrol station, or even making casual conversation with a stranger. These are mountains for Mercy, and Lock portrays them with unflinching tenderness and nuance.

Mercy is not fearless nor is she particularly hopeful. But she moves, because she must. Along the way, the landscape opens up in unfamiliar ways as she bumps into strangers with kind intentions and a series of mishaps.

Through each encounter, Lock paints a careful picture of what it means to live with persistent anxiety where even filling up a petrol tank feels like a mountain, and making eye contact feels like exposure.

What’s striking is how accurately the book captures the texture of living with mental health struggles – the panic attacks, the avoidance, the guilt, the frayed relationships, and the exhausting negotiations with yourself that accompany each day. Mercy’s internal world is as rich and restless as the terrain she drives through.

Lock captures the internal geography of anxiety with as much beauty as it does the Australian outback. She draws from her own lived experiences with mental health and reminds us that progress isn’t always dramatic. Sometimes it’s just making it through a day. Or stepping outside. Or saying yes.

Lock’s writing is sensitive without being sentimental. You feel the heat rising off the bitumen, the sharp relief of open space, and the tension of unfamiliar towns. There’s a realism here that resonates.

The people Mercy meets are imperfect, curious, sometimes helpful, sometimes not. But they are reminders that healing, however slow, is often a collective process. That the world, even when it feels hostile, still holds space for care.