“You seem to be from a different planet.” It was said half in jest by a college friend, but for Anima Nair, the words stuck. She had always processed the world differently, taking conversations literally, missing social cues, finding joy in the rhythm of words others skimmed past. Just over 2 years ago, she finally had a name for it: autism, a neurodivergent identity that has reshaped not just how she understands herself, but how she advocates for dignity and inclusion for others.

Today, Bangalore-based Anima Nair, at 51, is a writer, speaker, and advocate for neurodiversity, but that identity has been shaped as much by lived experience as by choice.

Misread in classrooms as arrogant, undone by the disorientation of early motherhood, and later confronted with the recognition of her own autism, she has had to dismantle deficit-based stories about herself and her son, and rebuild them through a strengths-based lens.

That process, of becoming, unbecoming, and becoming again, runs through every stage of her life: from childhood fascination with words, to the exhausting years of silence and self-doubt, to her current role guiding schools, workplaces, and communities to see neurodivergence not as a limitation but as a difference.

Becoming: Her childhood and early confidence

Anima’s childhood was both ordinary and otherworldly. Outwardly, she appeared serious; her photographs rarely show a smile. Inwardly, she lived in a world of endless invention: songs spun out of new words, playful verses about dinosaurs simply because their names fascinated her.

She excelled academically and assumed everyone else did too. Only later did she realize how her ease with learning made her seem aloof. “I’m sure that came across as dismissive. No wonder, through school and even college, I got labelled arrogant and proud. Mostly arrogant. I studied early, so I couldn’t understand why exams stressed them so much. I genuinely thought, If I can do it, why can’t you? That came from believing we were all the same.”

Early labels stick longer than the joy of dinosaur songs, leaving her with a sense of difference that she only began to name much later. [1]

College magnified that difference. Teachers praised her essays publicly, while peers teased her for missing cues. When a boy invited her for coffee, she took it literally, replying, “Oh, I don’t drink coffee.”

Humor softened the awkwardness, but the loneliness remained.

“I did enjoy hostel life, but fitting in was never easy. Friends would laugh at how I missed implied meanings, flirtation, sarcasm, and subtext. I always took things literally, and that meant I often felt apart, even when surrounded by people.”

College gave her the first realization that being “different” was not only about ability, but also about social rhythms that others seemed to understand instinctively. [2]

Unbecoming: Motherhood and burnout

Marriage came in her last semester of college, and motherhood followed, ushering in not a gentle transformation but a seismic upheaval. Her first child, Pranav, was born with colic and slept little, and the sleepless nights slowly eroded her fierce independence. Where she had once thrived on self-reliance, she now felt detached, unable to understand her own child or herself. The family was near but rarely supportive; their presence was marked more by criticism than comfort.

Over time, the weight of exhaustion and judgment blurred into a cycle of anger, despair, and self-pity that lasted seven years. “I was cursing God, asking: Why me? Why my child? I forgot to see the bright and very cute little boy who loved people and buzzed with energy. One day, I looked in the mirror and couldn’t recognize myself. The feminist, activist, go-getter was gone. I saw someone defeated. I had to tell myself to break the cycle.”

It was, as Joan Didion once wrote about grief, the feeling of inhabiting a different season of being, a season where the world looked familiar yet emptied of meaning.[3] For Anima, motherhood, mythologised as instinctive joy, felt instead like unravelling, a solitude made heavier by the chorus of others’ certainty. [4] The loneliest part, she says now, was not the sleepless nights but “the sense that everyone else was managing what I could not.”

In her words: “It shook me that even with education and privilege, I was drowning. I kept asking, if I feel this way, what about women with fewer resources, less support?”

Ocean Vuong writes, “Loneliness is still time spent with the world.” For Anima, those years were exactly that: time with her son’s unrelenting cries, time with her own reflection, time with questions that would not leave. Parenting had not come naturally. Instead, it left her broken, forced into a reckoning: sometimes the hardest person to mother is oneself.[6]

Becoming again: Writing, advocacy, and self-diagnosis

Breaking the cycle began pragmatically. Anima re-entered the workforce after a seven-year hiatus, taking a software job she didn’t love but needed.

“It wasn’t the job I was passionate about, but it helped me break patterns. I was happy to meet new people. I was happy to listen to praise. I was dressing up and showing up again.”

In parallel, she rediscovered writing. What began as casual notes turned into a weekly column. “That was the best job. A 500-word limit, but full freedom to write.”

She recalls: “I loved that space. I could write anything I wanted, every week. The freedom, the joy, the validation, it was rebuilding me. It reminded me I was more than a mother drowning in despair. I was a voice, and words gave me back my agency.”

Entering advocacy – Sense Kaleidoscopes and the seeds of change

As Pranav grew, so did Anima’s conviction that schools were failing children by focusing on deficits. With a partner, she co-founded Sense Kaleidoscopes [SK], channelling neurodivergent adolescents’ creativity into pottery and art products.

Yet, something troubled her.

“Our website would often showcase their diagnoses, their struggles, and less about their artistry. That was missing. I didn’t realize how much until I left Sense Kaleidoscopes.”

She remembers how often she was reminded she was “just a parent” without professional degrees. “My ideas on agency and autonomy were sidelined. I knew the art should speak for itself, but I struggled to find my voice against credentials. I stayed silent longer than I should have.”

Even well-intentioned projects can mirror the very hierarchies they wish to dismantle. Advocacy, Anima discovered, is as much about unlearning as it is about creating. [8]

Meeting Joel, Neurogifted, and naming herself

Leaving SK felt natural. “I was ripe… I fell when my time came, carrying seeds within me to plant another tree.”

That tree grew when she met Joel of Neurogifted. Through him, she encountered thriving autistic adults who were artists, poets, and architects, not case studies. It was liberating.

It was also unsettling when a colleague said, “Anima, you do know you are autistic, right?”

At first, she resisted: “I am not struggling. Others have real issues.” But in time, listening to self-advocates reframed autism not as a deficit but as a difference.

She recalls a turning point in Nepal, where a colleague gave her an article on how autism manifests in women. “It was not a DSM checklist; it spoke to lived realities. For the first time, I saw myself reflected. Still, it took a year before I could call myself neurodivergent.”

Sometimes it takes another to name what we already are. Accepting it requires not just confronting stigma outside, but unlearning the deficit narratives we’ve carried within. [9]

The other side of passion – frustration, tokenism, and apology

If Joel’s work showed her what inclusion could be, her broader experience revealed what it too often is: tokenism.

“Spaces that ‘scream inclusion’ but offer only a ramp at the entrance… posters of celebration days. That is not inclusion. That angers me the most, not when people admit they don’t know, but when they claim to know and then do the opposite.”

She adds: “What exhausts me is when minds are closed, when people loudly declare they already ‘know it all,’ while doing the opposite in practice. That shuts doors for learning. For me, humility is the real measure of inclusion, to admit gaps, keep listening, and keep growing.”

One of the most frustrating aspects of working in the autism space is seeing how many people still work in silos. “We don’t support each other enough. If something unfair happens to one member of the community, we rarely go beyond spouting standard responses. Personal focus still overrides community focus. So many times I have seen individuals leverage the community to get traction for their initiatives, but rarely give back.”

True inclusion is measured by the humility to admit what we did not yet know, and the courage to keep learning. [10]

When advocacy turns into appropriation

A book celebrating disability rights once carried her son’s art, but his bio reduced him to seizures and struggles. Consent was never sought.

“The story erased his process and presence. Nobody reading it would know my son beyond his disability… Consent matters. What someone may have been okay with a year ago does not mean they are okay with it now. We need to ask and not assume.”

She recalls the author justifying himself: the text had been copied from older content at SK. “Yes, technically true, but he never asked if I still wanted those words representing my son. His defensiveness and rudeness revealed how people who claim advocacy can silence parents, even erase dignity further.”

Representation without consent is not advocacy; it is appropriation. Dignity lies not only in what we say about others, but in whether we ask them first. [11]

Lessons from Pranav – sensory worlds and co-regulation

Pranav’s everyday questions reframed Anima’s understanding of autism.

“He would sometimes ask: ‘Should I wear a sweater?’ even in summer. Only later, I learned about interoception. He wasn’t being difficult; he was seeking co-regulation.”

This taught her to see quirks as adaptations, not defiance. “We are whole already… beauty emerges not because we are incomplete, but because together we create patterns richer and more vibrant.”

She explains further: “Earlier, I too thought of autism as a spectrum, arranged from high-functioning to low-functioning. But living with Pranav and naming myself autistic, shattered that. Our ways of processing the world are different, not hierarchical. What I once misread as oddity was really his body’s way of navigating signals that mine could not sense.”

What looks like an oddity may be an adaptation. To truly see another is to admit that our senses are not the only map of the world. [12]

The future she sees – schools, workplaces, and building inclusion

As a consultant on neurodiversity, Anima now works with companies to embed neurodiversity into structures, from hiring practices to architectural design. She recalls consulting on a metro station project in Ernakulam, where every floor was designed with sensory inclusion in mind.

But her heart remains in schools. “I want to show what is possible in classrooms, not just through accommodations, but through a strengths-based lens. It feels like my calling.”

She expands: “In workplaces, leadership may listen if they see productivity gains. But in schools, the shift is deeper; it is about planting seeds of dignity early, where peers, teachers, and parents learn to value difference. If we can change schools, we change the future workforce itself.”

Inclusion, as Anima envisions it is an architecture of belonging, built into walls, timetables, and the very ways we speak to each other. [13]

Final reflections – kindness, legacy, and living with dignity now

For years, she was haunted by the question: What will happen to my son after me? Today, the focus has shifted.

“I am less focused on after me and more on now. Dignity begins here, in the present. My role is not to shield him endlessly, but to be his scaffolding while he learns, fumbles, makes mistakes, and grows.”

She adds: “For so long, fear trapped me, imagining only incapability, worrying about absence. Now I see the power of letting go, of letting him try and even stumble. My legacy is not control, but coexistence. What I want to leave behind is not anxiety, but kindness.”

At the core, her legacy is simple: kindness. “Can we see everyone as part of one connected world without othering, disrespect, or differentiation? That is my story. That is my calling. And that is the legacy I wish to leave behind.”

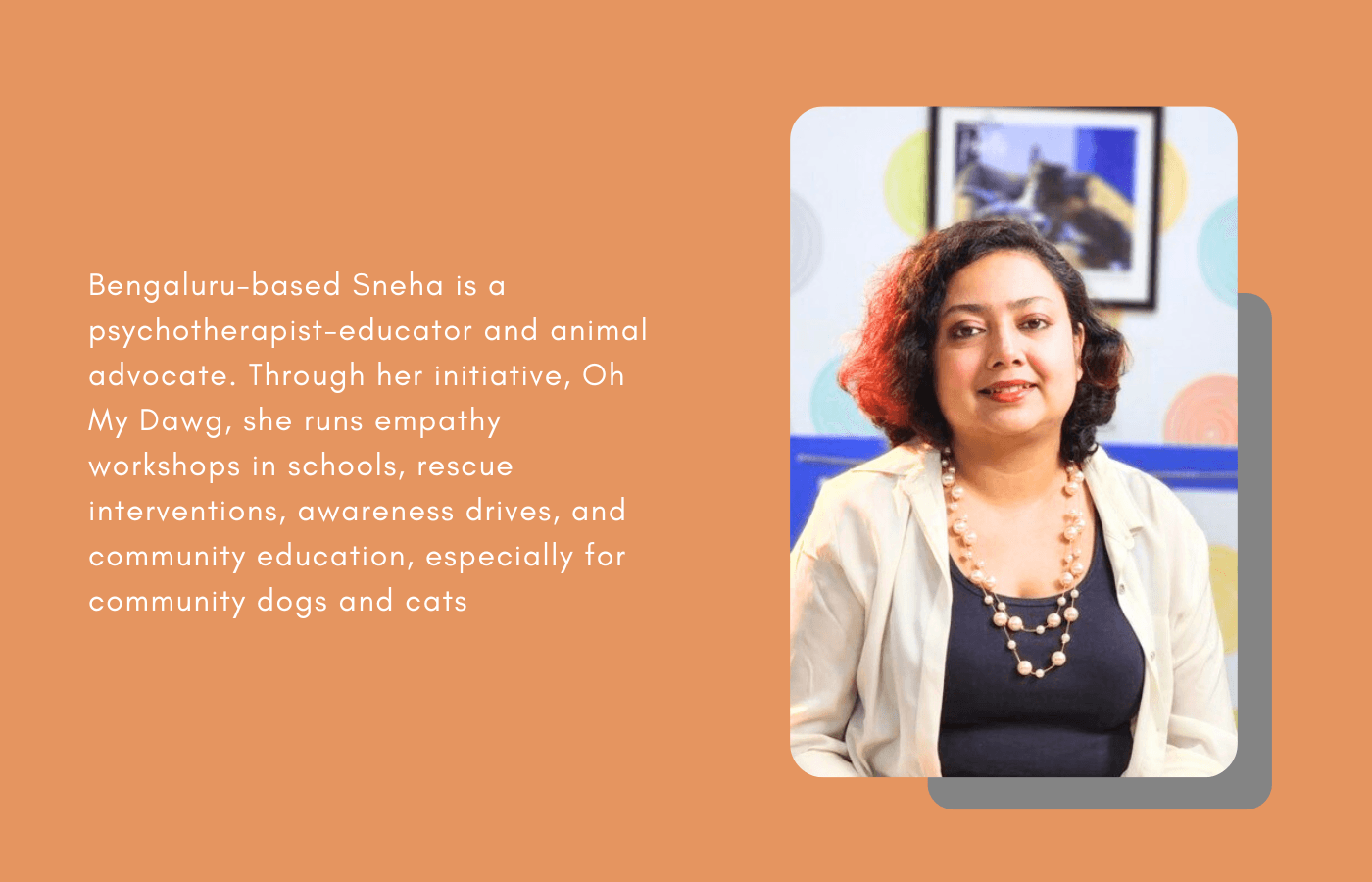

Note: Pictures in this article are representative and not related to the author.

REFERENCES

- Papandreou, A., Athinaiou, E., & Mavrogalou, A. (2023). Conforming and Condescending Attitudes of Gifted Children in Response to Their Social Anxiety and Asynchronous Cognitive and Emotional Development. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research, 50(2), 41539-41545.

- Millman, R. (2022). “More than a mask”: A multidimensional model of autistic women’s experience of camouflaging.

- Didion, Joan. The Year of Magical Thinking. Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

- Hem-Lee-Forsyth, S., Gabriel, J., N’Diera Viechweg, M. H. L., Kim, S., Sowa, F., & Bainey, K. (2023). Postpartum Burnout Among Women of Childbearing Age: A Neglected Global Public Health Problem. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Analysis, 6(09), 4396-4404.

- DeGroot, J. M., & Vik, T. A. (2021). “Fake smile. Everything is under control.”: The flawless performance of motherhood. Western Journal of Communication, 85(1), 42-60.

- Harding, M. (2024). Healing in Your Own Words; Self-Compassionate Writing for Post-Traumatic Growth.

- Morrow, a. (2022). Fostering student well-being: investigating the relationship between strengths-based teaching strategies and student attitudes towards life and learning (doctoral dissertation, Trinity Western University).

- Castañeda, C. J. (2023). Delayed and denied: a phenomenological investigation of women with autism and their experiences with late diagnosis.

- Setijaningrum, E., Kassim, A., Soegiono, A. N., & Ariawantara, P. A. F. (2024). Beyond tokenism, toward resilience: furthering a paradigmatic shift from intersecting narratives of disaster and disability realities in East Java, Indonesia. Cogent Social Sciences, 10(1), 2319376.

- Van Goidsenhoven, L., & De Schauwer, E. (2022). Relational ethics, informed consent, and informed assent in participatory research with children with complex communication needs. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 64(11), 1323-1329.

- Greenwood, B. M., & Garfinkel, S. N. (2025). Interoceptive mechanisms and emotional processing. Annual Review of Psychology, 76.

- Wehmeyer, M. L., & Kurth, J. A. (2021). Inclusive education in a strengths-based era: changing attitudes and practices. Człowiek-Niepełnosprawność-Społeczeństwo, (54 (4), 5-28.